Imagine a city that is livable for its citizens regardless of their income and socioeconomic status. A city in which neighborhoods are diverse and where participation of citizens is meaningful and welcome. A city that is harnessing its potential to reduce emissions, investing in vegetation and nature, and is prepared for heavy rains, water scarcity and urban heat. These characteristics reflect a resilient city.

The 55% of the global population living in cities accounts for over 70% of global emissions and consumes a large share of energy. As the world is increasingly warming, so are cities. Densely populated areas, concrete buildings and sealed soil all contribute to the urban heat island effect; this makes cities up to 3 degrees warmer during the day and up to 12 degrees warmer at night than their rural surroundings. The risk of flooding and water logging is also increasing due to more frequent heavy precipitation events.

Latin America has one of the highest degrees of urbanization in the world. Over 80% of the population lives in cities — a stark comparison to the 1950s, when this figure was 40%. This goes hand-in-hand with rapid urban growth, a lack of planned urban development and the degradation of ecosystems, as well as the marginalization of a large share of the population due to overall societal inequities.

What can urban resilience look like in such a context? Beatriz Lizarazu, an urban planner working for Helvetas Bolivia, sheds light on cities’ complex processes and promising interventions.

What are the greatest challenges facing Bolivia’s urban areas?

Currently, 68% of Bolivia's population lives in cities, and that number is expected to grow 10% by 2030. The urban population is concentrated in the main metropolitan areas (La Pax, El Alto, Cochabamba and Santa Cruz) and in medium-sized cities such as Sucre and Tarija.

Cities in Bolivia are primarily growing due to rural migration. This growth brings with it a series of challenges that plague many urban areas, such as informal settlements, difficulty in accessing basic services, socio-spatial inequality, environmental degradation and difficulties in urban mobility. Likewise, cities present conditions of multidimensional poverty associated with insufficient education, poor health, and informal employment or self-employment. According to the Urban Prosperity Index, Bolivia's urbanization process has developed in a sprawling manner with high land consumption, damaging the environment and natural resources.

Climate variability and climate change also have significant consequences for Bolivian cities. One of the biggest impacts is on water security, with the retreat of glaciers putting the water supply in the cities of La Paz and El Alto at risk. The loss of the Amazon ecosystem due to changing land use patterns has also led to a reduced water supply for the country's cities due to changes in the hydrological cycle. There’s also an increased risk of flooding due to the loss of vegetation cover.

Unfortunately, local capacities for urban planning and risk management are weak because there is no comprehensive, systemic view of the problems facing cities. The approaches implemented are unidirectional and often rely on traditional infrastructure. For example, the approach to conceptualizing green areas typically does not incorporate a nature-based solutions approach and, except for La Paz, urban land use planning does not incorporate disaster risk reduction management.

Which interventions have effectively addressed these urban challenges?

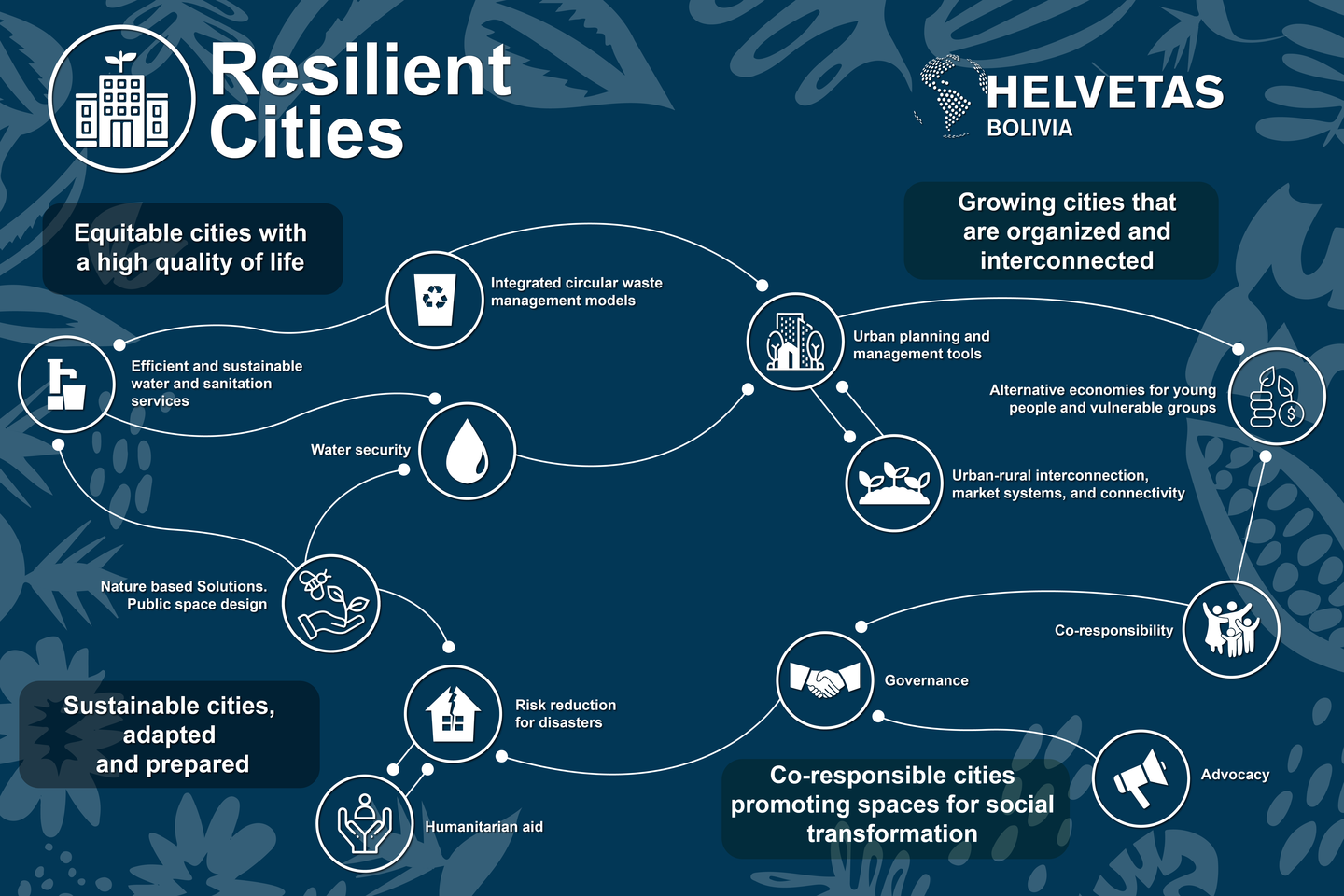

Helvetas is applying a resilient city model to tackle these complex problems. A resilient city has the capacity to maintain its essential services, meet the basic needs of its population, conserve and restore its natural ecosystems, plan and manage its territory to understand its vulnerabilities and manage its risks in a timely manner, and to address climate change, rapid urbanization and other emerging challenges.

The launchpad of the model is shaping policies. Local capacities are strengthened at different technical and academic levels to formulate comprehensive urban policies. Forty institutions and 15,000 people have now strengthened their urban planning abilities through training carried out in numerous projects.

Ensuring citizens play active decision-making roles is key. The CoRE Urban project launched the Urban Innovation Laboratory to promote citizen participation in generating solutions to the challenges facing cities. The “Ideathon” for Sucre was developed through this initiative. This competition invited 80 young citizens to propose ideas to make the city more climate-resilient, address water challenges and promote the use of public space.

Digital tools improve urban planning and risk management. The Disaster Risk Reduction Project developed the Investment Resilience Analysis tool, which evaluates projects such as irrigation systems, production systems and urban infrastructure to ensure they are resilient to climate change and natural disasters. The tool was institutionalized as a methodology to be applied to public infrastructure projects and is also used for development planning in all of Bolivia's territories to incorporate climate change adaptation and mitigation measures.

As part of the Resilient Cities I project financed by the World Bank and SECO, a digital risk map was developed that outlines the areas most at risk from landslides and flooding. It puts the emphasis on sectoral resilience by accessing databases on socioeconomic infrastructure, identifying the most vulnerable areas and sectors.

An app called “Alertas La Paz” was designed as an interactive tool to provide high quality weather forecasts, issue warnings for floods and landslides, and to allow citizens to report any hazards they witness in their neighborhood. This tool increases the population’s awareness of disaster risks and enables better planning, saving lives and assets.

The Basura 0 (Zero Waste) project generated circular models of solid waste management to quantify the emissions avoided through the proper final disposal of waste, developing a measurement tool. The Ministry of Environment and Water validated the tool, and a baseline was generated for all municipalities in Bolivia with a regression from 1974 to 2050 to generate scenarios and targets for the waste sector for the country's NDCs.

How do we ensure that urban development is benefiting all social and economic groups?

To ensure no one is left behind, all interventions must clearly define key actors and roles, adopt collaborative processes for the design and implementation of urban policies, create spaces for citizen consultation, and focus on responding to the needs of urban minorities, citizens in vulnerable conditions and those with less access to opportunities.

For example, the Basura 0 project identified grassroots waste sorters as key actors in the waste management system. This group was not considered in official waste regulations since they participate in this activity informally, collecting and sorting recyclable waste such as paper, cardboard, plastic, glass and metals for sale. The project strengthened the capacities of this group to reinforce their essential role in the system and support the improvement of their livelihoods.

The Chala-i project works with young migrants who have limited employment opportunities. The project collaborated with various actors from the public, private and civil society sectors to generate an inclusive policy that enables the development of youth entrepreneurship in vulnerable conditions, allowing them to improve their income, job skills and employability. This action benefited more than 1,000 young people.

Helvetas has developed a framework for urban resilience. How do you apply it?

Guided by Helvetas' experience, 13 cities in Bolivia are implementing models of resilient cities. The lessons learned and approaches generated made it possible to create this framework.

The model is applied through various projects developed by Helvetas in Bolivia. For example:

-

The Basura 0 project develops circular models for solid waste management in cities of various sizes.

-

The CoRE Urban project works on comprehensive urban planning and resilience in medium-sized cities.

-

The Kantutani project works on the design of public spaces based on nature-based solutions.

-

The Chala-i project promotes entrepreneurship to improve the living conditions of young people and boost urban economies.

-

The Resilient Cities I project works on disaster risk reduction through the development of risk maps and the strengthening of the Early Warning System in the city of La Paz.

-

The ARI and MIResiliencia projects develop methodologies for assessing sectoral and infrastructure disaster risks.

What would we like to see others working with urban populations do more of or do differently?

We need to prioritize interventions to make cities healthier and more livable. This begins with actions that reduce emissions and can be furthered by the nature-based solutions approach. This approach is being widely used in Latin America to generate biodiverse/green cities that, beyond the ecological benefits of ecosystems, guarantee public spaces that fulfill a public health function for cities and citizens — while leaving no one behind.

Another issue that is and will continue to be a concern for cities is water security, which could be achieved through the application of comprehensive water management approaches. This must also consider the challenge of rethinking efficient urban use in the face of growing demand and overcoming sanitation issues that have yet to be resolved.

There are also a lot of missed opportunities to facilitate better cross-sector exchange. The ideas are in place, but implementation is rarely aligned.

And last but not least, the area where most potential lies: Are we maximizing the use of collective intelligence? Sometimes the best solutions come from the citizens themselves, particularly young people. Let’s find more ways to promote young local leadership, recognizing the transformative potential of emerging professionals who know the territory and its dynamics.