In Bangladesh, thousands of men and women leave their village or even their country to find work. At the same time, thousands of men and women from Myanmar enter Bangladesh to protect their lives.

Migration has many different facets, as exemplified in Bangladesh and many other countries caught in cycles of mass emigration and immigration. It is just as much of a local and regional issue as it is a global topic. The most frequent type of migration is people moving within their own country—from rural to urban areas seeking work, as well as away from areas where living conditions have deteriorated due to climate change or violent conflict. Cross-border migration is also very common, with many people moving to a neighboring country.

To gain a more focused regional perspective on migration, Helvetas’ topic experts have published regional papers on migration and development for South Asia, Latin America and West Africa. These papers provide an in-depth exploration of geographic patterns, the numerous dynamics that fuel migration in each region, and the benefits and challenges that accompany the movements of migrants.

Migration patterns and corridors

Migration in large numbers often follows migration corridors. The biggest labor migration corridor connects South Asia and the Middle East. Bilateral agreements allow around 35 million men and women from Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and many more Asian countries to seek employment in Dubai, Saudi Arabia, and other countries in the region. Large flows of migrants can also be seen from Central Asian states like Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan to Russia, and from Central America to the USA.

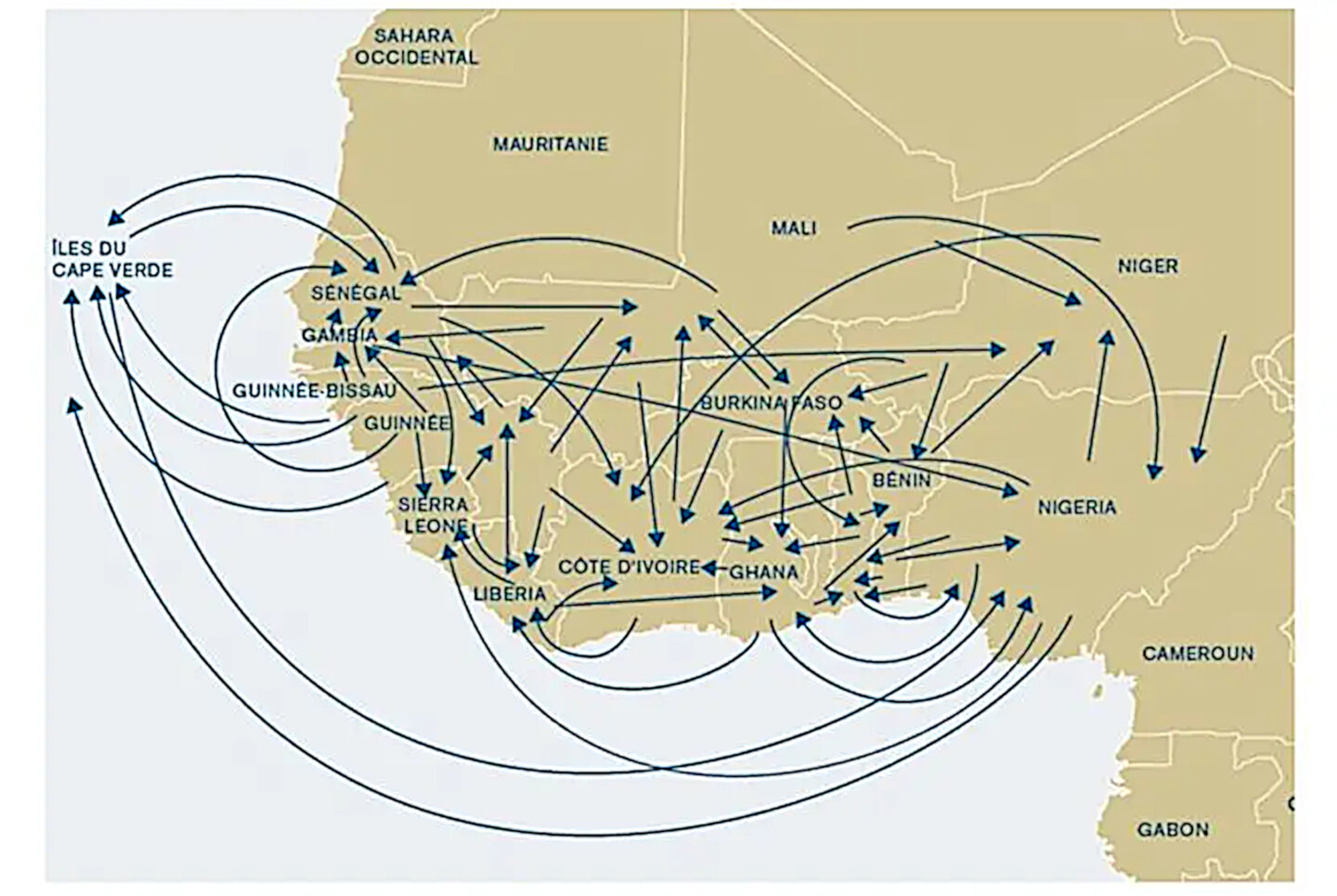

Research also shows that Africa is characterized by dynamic mixed movements where migrants and refugees take the same routes within and across the Economic Community of West African States’ (ECOWAS) free movement zone as well as the East African states. There are many different types of migration flows within the region, including domestic rural-urban movements, transborder mobility and pastoralism. The North African region is also a source of migrants aiming for Europe or the Middle East, serving as transit region and hosting an estimated 3.2 million refugees coming from various regions in Sub-Saharan Africa. About 20 percent of migrants aim to reach the Middle East or Europe, but the Africa Migration Report reveals that the majority of Sub-Saharan African migrants remain in the region and never embark on a journey to Europe.

Dynamics of migration

Labor migrants collectively send billions of dollars in annual remittances to support their families back home. This revenue stream can have enormous impacts on receiving countries; in Nepal, remittances sent by migrants from the Middle East make up almost 30 percent of the country’s GDP. The volume of remittances and their investment potential has also highlighted the critical need for migrants’ families to have financial literacy.

Though the promise of remittances can be life-changing, labor migration can lead to great hardship for those left behind. “My wife is abroad. I wanted to give my two daughters to the children’s home, as I found it extremely difficult to bring them up, manage the household chores and at the same time continue my daily labor activities,” said Mr. Janaka from Ambalangoda in Sri Lanka. He was supported though the safe migration project Helvetas implemented on behalf of the Swiss Development Cooperation in Sri Lanka. “I sought counselling with the clinical psychologist who discussed different options with me. I realized that a children’s home is not preferable if not absolutely necessary. I still find it challenging to manage the household, but have been introduced to support mechanisms.”

Labor migration also carries great risks for workers, particularly for women. South Asian migrants are vulnerable to mistreatment and exploitation by employers, as evidenced in the account of Asmi, a migrant from Batticaloa in Sri Lanka who is a Helvetas project participant. “I worked in Saudi Arabia for two years but did not get paid and was always told that the salary will come soon,” she said. “After two years I managed to escape with the help of a Pakistani taxi driver and fled to the Sri Lankan Embassy.” Asmi’s story is far from an isolated incident; Saudi Arabia consistently ranks as one of the most dangerous places for South Asian migrant workers.

The many faces of forced migration

Those who migrate because they are forced to leave their homes due to conflict, violence, persecution and human rights abuses are yet another large group ending up on dangerous routes or in refugee camps within or beyond their countries of origin. According to the UN Refugee Agency, in 2020 more than 80 million women and men were forcibly displaced worldwide. Migrants from Central America find themselves in mixed migration movements in which forcibly displaced and people fleeing poverty are travelling together. Among other things, they often claim that they just could not live safely in their homes due to the extreme amount of violence by gangs as well as security forces, all of which is exacerbated by corruption.

Women and men are also lured into exploitative working situations by middlemen using fraud, force and coercion for exploitative purposes, which is called trafficking. This is an organized crime extending beyond boundaries and jurisdictions, and Helvetas is working to address trafficking in Sri Lanka through a project financed by the US Department of State.

Bangladesh offers another example of a complex web of emigration and forced migration. It is a country of origin for thousands of labor migrants to the Middle East and across the border to India. But the country also hosts the largest refugee camps in the world, which are home to almost a million Rohingyas who have fled the violence perpetrated against them in Myanmar and sought refuge in Bangladesh.

Bangladesh is also heavily affected by climate change due to its low elevation (80 percent of the country lies in a flood plain), high population density and poor infrastructure. Increasing numbers of women, men and children are being displaced each year by extreme weather such as cyclones and floods.

-resident of Gabtola, Morrelganj Upazila, Bangladesh

A triple win

Well managed and safe migration can benefit the country of origin and the country of destination, as well as the migrants and their families—if good migration governance structures are in place. Global international remittances reached $689 billion in 2020, supporting families back home. Many returning migrants and their families have benefitted greatly from the migration experience and the support they received, and numerous prospective migrants could secure better jobs and higher payment because of previous professional training. Migration also brings additional workforce, know-how and ideas for the receiving economies and new skills for migrants.

But international migration comes with tangible social and human costs as well as various risks. Helvetas’ approach to migration strives to understand the regional and global dynamics of migration in an effort to make migration work for all. The regional migration and development papers serve this guiding purpose and offer evidence and insights on how we can maximize migration’s positive impact on development.