Tracer studies are a powerful monitoring and evaluation instrument to gain information about the relevance and effectiveness of vocational skills training projects. As the name suggests, graduates are traced months after the completion of their vocational training to see where they are at: Has the training led to employment and a better income? Can the graduates use the skills they acquired during the training in their current jobs? How useful was the training?

Tracer studies serve a dual purpose: While the graduates’ feedback helps projects and training institutions to improve the quality and effectiveness of their programs, the studies also generate compelling evidence on the effectiveness of projects. In an era of funding cuts for development assistance, it is more important than ever for projects to be able to make the case for their continuation.

Lack of training opportunities

In Mozambique and Tanzania, there is a lack of job opportunities for young people. According to International Labour Organization, 850,000 young women and men in Tanzania enter the labor market annually, but only find 50,000 to 60,000 formal jobs available.

Both the SIM! project in Mozambique and the YES project in Tanzania give young women and men the opportunity to undertake short, practical training courses that are geared towards the local market and support them as they begin working life, either starting their own business or finding employment. Though Mozambique and Tanzania share similar struggles in the lack of employment opportunities for young people, the struggles of youth in Mozambique are further compounded by the country’s limited economic growth, conflict and more political instability than its neighbor, especially in the north.

Highlighting the effectiveness of skills projects

The YES project Tracer Study (2024) and the SiM! Tracer Study (2024–2025) both evaluated vocational training outcomes for marginalized youth. The YES study, conducted after 1.5 to 2 years (at the project’s mid-term evaluation), surveyed 250 graduates in Tanzania’s Dodoma and Singida regions who participated in a structured vocational training program.

In contrast, the SiM! study was carried out 6 to 12 months after training was completed and assessed 95 graduates in the Nampula province of Northern Mozambique. Both studies provide promising evidence of the effectiveness of vocational skills development training on employment and income outcomes.

Employment and income outcomes

One of the key findings of the YES study was that youth gained additional streams of income following their completion of the training. Prior to the training, 64% of the youth earned 20 USD per month or less (22% had no income). This number reduced to 21% (10% having no income) after the training (see blue and orange parts of the pie chart). Even more impressively, only 8% earned above 40 USD per month before the training, which increased to 52% after the training.

Vocational training programs are not only equipping young people with market-relevant skills, they’re also delivering tangible improvements in their livelihoods. In Tanzania, 88% of graduates said they were satisfied with their current employment. And in Mozambique, 96% of trainees reported that their personal situation had improved following their graduation.

One of these trainees is 21-year-old Nuro Mamade. After the training, he continued to work in his trainer’s shop, using his tools, while also attending to his own customers. The money he saved allowed him to buy the tools he needed to open his own carpentry shop.

Evidence of growing entrepreneurial confidence was also found in Mozambique. Many trainees shared that they now had the skills and motivation to start and maintain their own businesses — a crucial mindset in a context where formal jobs are scarce.

The persistent gender gap

The studies in both countries show that gender gaps in income persist despite programmatic efforts to overcome them. One measure to improve employment and income outcomes of female graduates is the application of the results-based financing approach. This approach encourages training providers to help young women to enter the labor market after the completion of training by linking them to potential employers or helping them starting their own businesses.

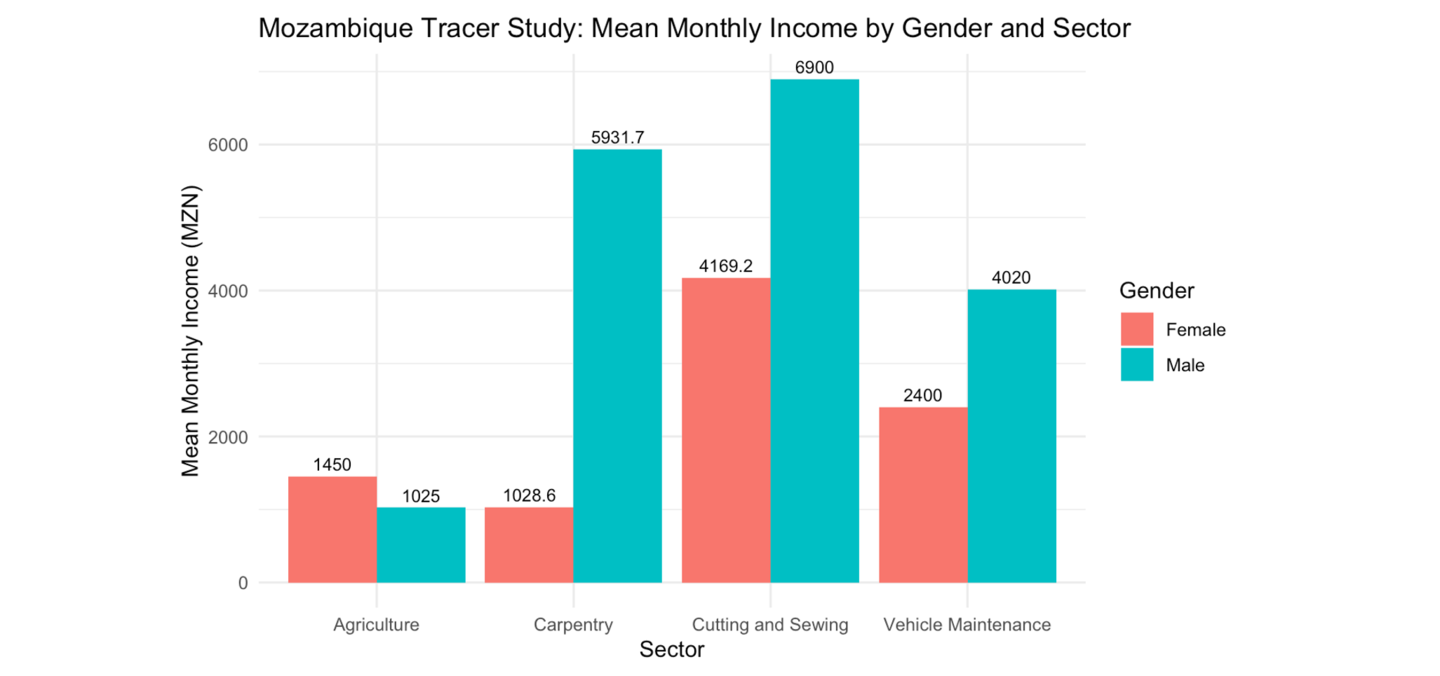

In Tanzania, even though women see greater relative gains in income after training (especially those escaping the lowest income brackets), men still have the edge in reaching the highest earning tiers. And in Mozambique, men working in the same sector as women (e.g., carpentry, cutting and sewing, and vehicle repair) reported earning a higher income.

Challenges remain

The studies also highlighted problems that young people still face, despite their training, to enter the labor market. In Tanzania, 12% of youth reported that after training they still struggled with a lack of capital, limited customer base, a lack of support to start their own businesses, and low wages.

Zumrath, a graduate of the YES project, owns a small tailor shop in Tanzania’s central corridor. She says that despite having a solid customer base, her business is very seasonal. Most of her sales are around holidays and during harvest season, when people in her community comprised mostly of farmers have money to get clothes made or altered. She cannot charge customers high prices since they otherwise couldn’t afford the clothes, which leaves her with small margins.

In Mozambique, youth highlighted their most pressing issues as a lack of customer demand and workshops to continue honing their skills after the training has ended.

As these two country examples show, tracer studies offer valuable insights into the real-world impact of vocational skills training on youth employment and income. They demonstrate that despite significant structural challenges and limited formal job opportunities, practical vocational programs can yield meaningful improvements in livelihoods. However, the persistence of gender-based income disparities and barriers such as a lack of capital, inadequate workspaces and fluctuating market demand point to the need for the continued strengthening of support systems — such as follow-up services, access to finance and more inclusive job pathways.

About the Authors

Ariea Burke conducted the tracer study as an intern for the SIM! project in Mozambique.

Doreen Kimbe is a Project Officer for Monitoring and Evaluation for the YES project at Helvetas Tanzania.