It is the apple harvest in Jumla; trees are laden, and at the little airport where we waited for our outgoing flight, boxes of apples were stacked waiting to be squeezed into the hold. Jumla is renowned for its apples – but sadly, apple farmers tend to make thin profits. All the fruit ripens within a relatively short time frame, and prices plummet. Storage is problematic, and transport down the pot-holed Karnali “highway” to the markets in the South results in up to 50% wastage. There are some enterprising attempts to produce dried apples, apple jam and apple brandy, but these are relatively small-scale.

This context is an important one for Helvetas’ Mito project, which with funding through the Happel Foundation is working to support the walnut value chain.

Walnuts: soft- and hard-shelled

There are two types of walnut in Nepal: soft-shelled (thin-shelled would be a better description), and hard-shelled. The former is cultivated by grafting high-yielding, soft-shelled walnut stems onto hard-shelled rootstock – a difficult process that until recently had a very low success rate. The hard-shelled type grows wild in Jumla forests, some of which are government owned and managed, whilst others are managed by community forest user groups. The nuts are traditionally harvested for oil in a messy, very time-consuming process, typically done by women.

Tara Devi Sarki, walnut collector and member of a producer group

Walnut oil extraction

In 2017, two Swiss students set about designing a simple walnut cracking machine that would mechanize oil extraction and thus substantially reduce women’s drudgery. The cracking machine, powered by a bicycle, received much attention in the Swiss media, and demonstrated considerable technical ingenuity. Nevertheless, its introduction in Jumla coincided with rural electrification, and women were naturally keen to plug the machine into a socket rather than to pedal. That development was prototype 2; currently Mito is working with a group of producers on prototype 4, in an iterative process of improvements. We will test the latest version of the machine during this year’s harvest.

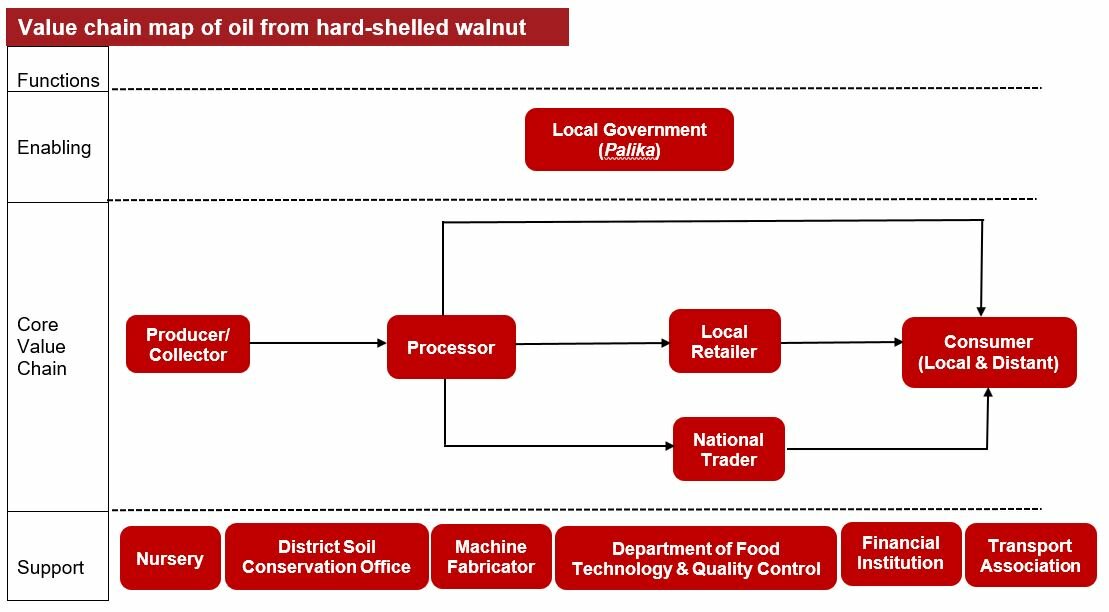

Meanwhile, we have explored the whole value chain for walnut oil (see value chain map), identifying key actors and challenges. In addition to several walnut producer groups, Mito is working with three local municipalities (two rural, one urban), which are so convinced of the potential of walnuts that they are contributing their own funds to a walnut-processing center. They also have plans for a substantial walnut plantation. Both commitments bode well for the sustainability of production. Regarding sales, although there seems to be some potential to sell oil to passing tourists, the most promising market lies outside Jumla, with a Kathmandu-based company. This company, which specializes in forest-based products, has already put in an order for this year’s walnut oil. It is also including walnuts in an up-coming organic certification of products that it sources from Jumla (the district self-declared itself organic in 2007, but certification is important for many buyers).

Walnut kernels

Soft-shelled walnuts show clear income-generating potential. Unlike apples, they store well and are easy to transport. Currently prices are high; whilst apples are selling locally at NRs 40/kg, whole walnuts fetch NRs 600/kg (USD 0.3 and 5 respectively). Traders in the bazaar say that they can sell more, as do members of several agricultural cooperatives. Nursery owners are doing good business: grafted apple seedlings currently sell at some NRs 40 – whilst grafted walnut seedlings fetch up to NRs 650. Working with the local horticultural research station (run by the National Agriculture Research Council, NARC) and with experienced nursery owners, Mito has facilitated the perfection of walnut grafting techniques. Survival is now around 85%, against an earlier survival of below half – and farmers are keen to plant more grafted stock. Although yields vary from year to year, average production from a mature tree (over 10 years) may reach over 60 kg, and production starts within 4-5 years.

Poverty focus

In working with two types of walnut, Mito offers different livelihood enhancement opportunities. Even the poorest and most socially discriminated can harvest hard-shelled walnuts from local forests and join producer groups to extract the oil. Currently harvesting is free, although that may change if the oil becomes commercially viable – in which case the producer groups will need a strong voice to negotiate with the government. Meanwhile just a few soft-shelled trees can provide a small farmer substantial future income.

“Take home” messages

The Mito experience clearly illustrates several points that are neither surprising nor unknown - but are nevertheless worth emphasizing. These are that:

- Introducing new technology to people living in remote settings generally requires much testing and modification to achieve a satisfactory result

- A full understanding of any value chain is essential before intervening; being sure that there is a market, and access to it, for the intended product is clearly crucial

- Market diversification is a wise step towards greater income security for small farmers.