“It is impossible to discern political parties from public institutions. Many decisions are made by political parties, and then public institutions only confirm them formally. Hence, they are the most influential. Non-governmental organizations, unfortunately, do not have the influence they are supposed to have. The CSO [Civil Society Organizations] sector is fragmented, without strong coalitions; sources of funding are not sustainable; donors change priorities,” says Aleksandra Petrić, “United Women” Foundation, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

This statement mirrors the trend of shrinking space for civil society - a metaphor that describes restrictions on the institutional and political environment in which CSOs operate - across the Western Balkans. The trend is concerning despite the fact that negotiations for European Union (EU) accession provide an opportunity for civil society to advocate and propose policies to the government, particularly on human rights issues, which constitute a major part of Chapter 23 in the EU acquis.

In this article, we would like to share with you our understanding of why the space for civil society is shrinking in the Balkans, building on two well established monitoring references and ending with potential ways for reshaping the space.

6 features of the shrinking space for civil society in the Western Balkans

Based on literature research, interviews and personal work experience, we see six common features that exacerbate the continuing decrease in space for civil society in the Western Balkan region:

Feature 1: Legal and policy frameworks are largely in place, but not yet adequate to provide for a conducive CSO environment. Their poor implementation also imposes restrictions. As a result, partnership relations between CSOs and governments are stagnating.

Feature 2: Negative rhetoric and repressive measures of the governments against CSOs were particularly strong in some countries during 2018. Nations in Transit notes that Presidents of Serbia and Montenegro have “captured their respective states, turning them into mechanisms for distributing patronage that in turn strengthen their parties’ grip on power.” CSOs struggle to make their voices heard, and those expressing criticism of governments are often subject to harassment.

Feature 3: Media freedom has come under threat in the recent years. Intimidation against journalists is increasing, which suffocates investigative journalism.

Feature 4: International donors are still present but the amount of funds for CSOs has decreased. Funds for development assistance are often channeled through public institutions and international agencies, which then act as mediators (grant managers), not directly through CSOs. The decreased funding affects CSOs' sustainability.

Feature 5: Limited demand by CSOs in claiming their space and poor participation in existing spaces result in little influence on decision-making and democratic processes. The polarized, fragmented, financially unsustainable and under-capacitated CSOs cannot articulate strong demands towards the governments.

Feature 6: Capture of CSOs by the political elite is omnipresent. Spaces traditionally inhabited by CSOs are captured by private interest groups and government-oriented NGOs (GONGOs) that are often affiliated to political parties.

Many of these features overlap and CSOs experience them simultaneously, compounding the problem.

How to measure the (shrinking) space?

For the Western Balkan countries, the two frequently used methodologies are the CSO Sustainability Index and the CIVICUS Monitor.

The CSO Sustainability Index methodology was designed under the assumption that “CSO sustainability would improve across all countries and regions, and that those with lower levels of sustainability would eventually catch up with those with higher levels of sustainability.” Today, however, the scores are converging towards the middle of the scale.

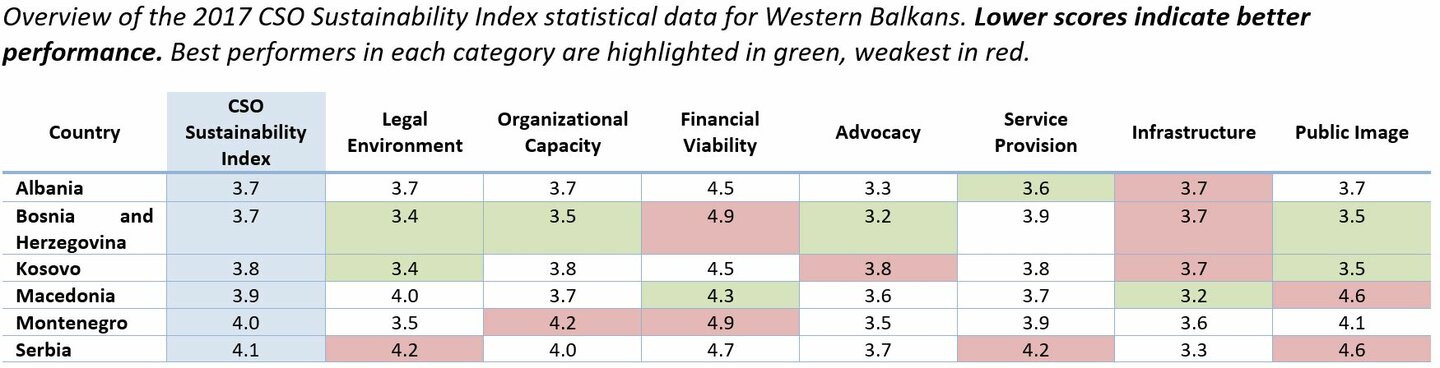

Data on civic space are collected in all countries to populate the indicators along seven dimensions. Then, according to the scores, countries are clustered into three stages: Sustainability Enhanced, Sustainability Evolving, and Sustainability Impeded.

The 2017 CSO Sustainability Index scores indicate that all six Western Balkans countries fall into the Sustainability Evolving stage. Analysis of scores over previous years leads to the following conclusions:

- Legal Environment slightly improved in Albania (there is still a need to adopt legislation to decentralize registration, and improve fiscal treatment and funding opportunities of CSOs) and Kosovo (improved public system of financial support for CSOs), whereas it deteriorated in Serbia (for the third year in a row due to increased impediments to the work of CSOs; space for CSOs and media operations continued to shrink) and Macedonia (critical CSOs were subject to extensive state harassment).

- Organizational Capacity of CSOs stagnated in most countries. The CSO institutional development is hampered by significant staff turnover and limited resources to train new staff; scarce funds generally go towards project implementation.

- Financial Viability is the weakest dimension in all countries, but there was a relative improvement in Kosovo (new international funding programs and more CSOs with sound financial management systems and procedures), Macedonia (increases in local philanthropy) and Montenegro (new mechanism for public funding of CSOs).

- Advocacy is the strongest dimension in all countries, with the ascending trend in Macedonia (CSOs responded to many developments in the country and led coordinated advocacy efforts) and the descending trend in Kosovo (fewer opportunities in the election year) and Serbia (the ability of CSOs to engage effectively in advocacy worsened for the third year in a row).

- Service Provision improved in Albania (increased number of CSOs providing services to their constituents and the state increasingly recognizes this role of CSOs), Macedonia (CSOs continue to provide a range of social services; cooperation with state institutions improved) and Montenegro, while the others are stagnating.

- Infrastructure improved in all countries, except for Kosovo (support services are insufficient and generally not available outside the capital).

- Public Image of CSOs stagnates in most of the countries; improvements were registered in Montenegro (businesses started to perceive CSOs as valuable actors in community development).

The CIVICUS Monitor analyses the space for civil society in every country of the world along the three core freedoms of: (i) Association, (Ii) Peaceful Assembly, and (Iii) Expression, with in-built understanding that a state has a duty to protect civil society and proactively facilitate citizens' enjoyment of their rights. CIVICUS produces a guiding qualitative score for each country that is used to assign ratings: Open, Narrowed, Obstructed, Repressed, and Closed.

According to the December 20, 2018 update, the CIVICUS Monitor ratings of all Western Balkans countries are the same – ‘Narrowed’ civic space. This means that the states allow individuals and CSOs to exercise their rights to freedom of association, peaceful assembly and expression; however, violations of these rights also take place. The respect of the core freedoms was assessed as follows:

- Association: Legal and policy framework that facilitates the right to association is generally in place. However, several issues remain problematic, such as the centralized and costly registration of CSOs in Albania, unfavorable legal changes proposed in the draft Law on Freedom of Association in NGOs in Kosovo and draft Law on Social Entrepreneurship in Serbia. Human rights defenders are subject to attacks and pressure from the government, especially the LGBTIQ groups, Roma, organizations that support migrants and anticorruption CSOs. Funding is generally low, state allocations are not transparent and CSOs mainly rely on international funds.

Positive developments were registered in Macedonia with the adoption of the Strategy for Cooperation and Development of Civil Society 2018-2020.

- Peaceful assembly was exercised in all countries, mainly in the form of protests on environmental issues (e.g. construction of hydropower plants) and political controversies. Some protests turned violent in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia and Serbia, and government reactions were suppressive rather than open to change.

- Expression: In all countries, the right to freedom of expression, especially in regard to the media, is in decline. Defamation is used against journalists leading to a dearth of investigative reporting, particularly in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania. Media is generally assessed as heavily influenced by political and business interests.

Ways for reshaping space

It is likely that the civil society sector in the region will remain dynamic to respond to political and social changes, while actors will continue to struggle for spaces. The spaces will be rearranged, opened up and closed down at times. For CSOs to take advantage of these dynamics, it is important that they investigate the underlying causes of the shrinking space and what stake each actor has in the struggle. A concerted response of CSOs should be based on new relationships with other sectors (e.g. developing multi-stakeholder initiatives), including engagement with the private sector, transparency, respect and a shared commitment to advancing common goals. CSOs cannot continue to run ‘business as usual’. They must design strategic actions, build new capacities, networks and new organizational culture to get to grips with everchanging environments.

A possible scenario is that the civil society sector will diversify per country, which would require a tailor-made design of approaches in development interventions and research of civil society practices. However, history has taught us that, in any context, grassroots and community collective actions need special attention, as these will remain the greatest force for inciting substantial social and political changes. How do you see your role in supporting an active civil society? Have you considered the implications of your work and interventions on civil society?

This article appeared in the March 2019 issue of Helvetas Mosaic.

Note

The starting quote is taken from Živanović, A. (2019). Uloga organizacija civilnog društva u procesima tranzicije – protivrječnosti situacije u Bosni i Hercegovini [The Role of Civil Society Organisations in Transition – Contradictions in Bosnia and Herzegovina] (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Banja Luka, Faculty of Political Sciences, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Subscribe to Helvetas Mosaic

Helvetas Mosaic is a quarterly published by Helvetas Eastern European team for our email subscribers and website visitors. Our articles explore new trends and fresh ideas of international development work in Southeast Europe.