Knowledge is universally seen as an important asset. Its mere accumulation, however, doesn't generate much value – how it's used matters. Therefore, ‘Learning and adaptation’ are necessary and accompanying actions that turn knowledge into something useful.

In development cooperation we aim to utilize knowledge for wider social benefits – something we mostly refer to as ‘impact’. How organizations learn and translate learning into action facilitates their ability to succeed in a complex and dynamic world.

To take it a notch higher: how societies generate and exchange knowledge and the extent to which it's accessible and utilized for public discourse and decision-making facilitates their ability to generate wealth.

Most readers will agree with the above. But if this is so uncontroversial, why is it that so many development projects fail to achieve significant impact? Why is it that transitioning knowledge to decision-making remains a privilege that only serves a few in so many countries? And that so many important decisions are ill-informed and not based on evidence? What can be done about this?

To answer these questions, we distinguish between the institutional and the social dimension, understanding that the one builds on the other - how learning and adaptation happens in institutions (public/private, formal/informal, permanent/temporary etc.) - is of great significance to how societies as such are able to adapt to new circumstances.

But first, let’s talk about impact

Increasingly, development practitioners and policy makers refer to ‘impact’ as the social benefits that result from causal actions and relationships between different actors and institutions in a given context. We would often talk about systemic change that is socially inclusive. In fact, this year’s Nobel Prize for Economics has been awarded to three scientists whose research has been instrumental in understanding causalities and breaking these down into more manageable questions for effective development interventions.

For example, the ability of a young woman to find a job and pursue her career ambitions depends not only on her ability to access relevant education, but also the protection of her rights during pregnancy and maternity leave, the availability of childcare services and even social norms and perceptions about the role of women in society in general. To effectively enable equal access to income and employment opportunities for women, development cooperation needs to understand the system of causalities that undermine their economic participation and find feasible entry points for facilitating change. Whether or not a project achieves ‘impact’ therefore is dependent on its ability to address different strands of causality influencing the performance and social inclusiveness of the overall system.

‘Achieving impact’ then becomes less straight-forward than what many theories of change make us believe as impact isn't only the jobs or higher incomes resulting from our development efforts. Rather it's understood as the changes in different and interrelated causal factors and relations that influence the way how certain systems (such as education) perform and are accessible to all. Often this's referred to as ‘system change’. Achieving this kind of ‘systemic impact’ is difficult and complex – and requires continuous learning and adaptation, recognizing that knowledge is always incomplete, and realities always change.

Looking at how impact and learning functions in institutions

Every organization needs to have some form of system in place that enables it to assess the subject and context of its work and translate this into decision-making that affects the course of future actions. The more such a system is integrated into organizational systems, procedures and culture, the likelier it's to maintain a competitive advantage over others and/or be more effective in achieving its objectives and/or being more effective in doing no harm. Companies, therefore, invest significant resources into R&D to grow their market share. Government agencies commission research for more effective and inclusive policies or develop M&E systems for their social programs. More and more development projects have monitoring systems for interventions that aim at system change (such as the DCED Standard which Helvetas applies in many of its projects). Hence, learning and adaptation based on different types of evidence (depending on the question at hand and corresponding methods/design choices) is key to success across different sectors.

Many development interventions don't work, and one – not the only but an important – reason for this is the lack of a functioning internal system for learning and adaptation.

Kimon Schneider, Senior Scientist from NADEL, the Centre for Development and Cooperation at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich mentions several reasons for this. Some of them are:

- An underinvestment into capacities and resources needed for an effective monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) system (or underinvestment in R&D in other organizations), be it in terms of developing such a system (conceptually, digitally etc.) or bringing everyone to using such a system (capacity building)

- A disconnect between the MEL system and decision-making processes (or disconnect between R&D and other departments of another organization) implies that collected data is mainly used for reporting purposes rather than learning and steering

- An organizational culture that hampers learning and adaptation – for example extremely rigid approval processes, no space and time for evaluative and creative thinking, non-acceptance of failure and risk-taking, i.e. the lack of a learning culture, etc.

- People who don't ask questions and lack the creativity required to translate evidence into learning and adaptation

Other organizations may find that political agendas prevail over the use of knowledge generated through MEL, that knowledge generated by MEL is often not accessible and sufficiently tailored towards decision-making, or that qualitative shortcomings in how knowledge is generated means that it isn't perceived as being credible enough for decision-making.

Organizations need to invest into the development of capacities and the systems and procedures that allow them to generate new and/or capitalize on existing evidence (collection and evaluation and synthesis of relevant data and information) and feed it into learning and decision-making. This should consider the needs of different actors at different levels of an organization: at project, portfolio, regional and organizational level and allow up- and downward flows of knowledge. Supportive leadership is an important factor in this endeavor: to enable a conducive organizational culture for learning and adaptation, managers (from field to policy level) need to create the space in which staff can challenge established practices and knowledge and engage in a meaningful and creative discourse based on ‘evidence’ generated through MEL.

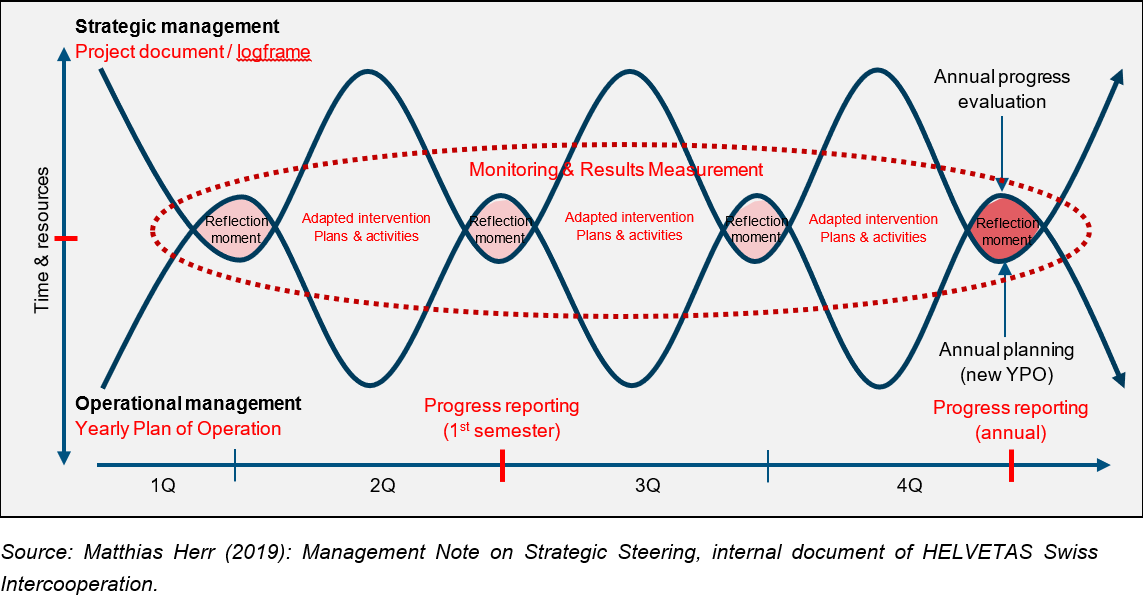

Understanding why things work or don’t work (learning from failure) and translating this into evidence-informed policy-making and programming (i.e. adapted planning and implementation and evaluation) is key to successful development projects as it is also for other organizations in other sectors. This requires a common understanding between implementing agencies and donors: most importantly, allowing projects a high degree of operational flexibility while remaining committed and accountable towards achieving sought results. The figure below illustrates how operational and strategic management converge around ‘reflection moments’ built into yearly project cycle management, and how these are informed by a knowledge management and learning system that builds on M&E. Such a process is similar at different levels of an organization and applies to different type of organizations in different sectors.

But this is not where it ends…

While it's a well-established (though surprisingly often ignored) fact that organizations require evaluation capacities connected to learning and decision-making, less attention is given to the importance of knowledge flows between organizations. The social dimension of MEL.

Dr Stefanie Krapp, Head of the International Program for Development Evaluation Training (IPDET) at the University of Bern calls this ‘systemic evaluation capacity’, referring to a system whereby different actors in a sector collaborate by conducting targeted evaluations, gathering data and information at different levels, and exchanging this for improved sector-level outcomes.

For example: public and private institutions in the healthcare sector (such as Ministry of Health, municipal authorities, hospitals and NGOs) establish an evaluation system that generates evidence at different levels to inform more effective reforms and policies at national level. Or, formal and informal private sector businesses and membership organizations that collect and process data and use such evidence to advocate for business environment reforms towards political decision-makers in the executive and legislative branches.

Imagine a complex social network of people and organizations with nodal points where knowledge is aggregated, processed and used for the purpose of influencing others. It's characterized by pluralism: different groups equipped with ‘alternative facts’ that underscore their positions and are used to engage with others in a public discourse of competing ideas and intentions - the very notion of democratic decision-making and the functioning of a market economy.

Just as organizations require a functioning system that enables evaluation, learning and adaptation, society requires systems that allow for more effective use of knowledge (or evidence) to cope with an ever-changing and more complex world. IPDET refers to this as ‘Evaluation Capacity Development’ (ECD), including everything required to institutionalize evaluation structures and processes within relevant actors such as state, private sector or civil society groups. ECD must be implemented at different levels, using instruments that are appropriate for capacity development at the level of individuals, institutions as well as a conducive environment – and inter-linkages between these levels.

Faster cycles of technological innovation for example pose a challenge towards countries that compete based on low-wage labor: several studies show that the Future of Work relies mostly on a skilled workforce and an education system that can quickly respond to changing requirements and enables life-long learning. This requires a ‘systemic evaluation capacity’ feeding into national level discourse and decision-making on adaptation of education systems.

The problem in lower and middle-income countries such as the Western Balkans is that knowledge flows are dysfunctional and often captured by a small and influential minority, leading to ineffective policies and reforms or exacerbating social exclusion. The underlying causes can be summarized as follows:

- Poor evaluation capacity of key actors: this refers to what we mentioned above and requires and investment into organizational development – particularly in those nodal points in the system that have a knowledge aggregation and dissemination function

- Underlying power structures and relationships that either inhibit access to knowledge for some and/or prevent its use to be translated into a transparent discourse and decision-making process, with critical institutions often captured by a small (and corrupt) elite segment that caters to its clientele only

- And along these lines: missing or weak structures that enable more effective interaction between different actors including the degree of organization in a sector, infrastructure and platforms for communication, the use of modern communication technology, learning and sharing

- A general absence of critical / evaluative thinking, often as a result of how education systems function in a country (authoritative teaching methods vs teaching understood as stimulating independent learning and critical discourse)

Development cooperation needs to focus more on stimulating knowledge-based systems that enable evidence-informed decision-making. The flow of knowledge and information between actors is crucial for the ability of societies to remain resilient and competitive in a faster changing and more complex world. Building the ‘systemic evaluation capacity’ needed to achieve this requires knowledge management and learning systems at different levels as promoted by IPDETs systemic approach to ECD.

In conclusion

Every organization requires a knowledge management and learning system to enable effective (evidence-informed) decision-making and programming and secure a valid role for it. Setting up effective knowledge management systems often falls victim to the nature of the short-lived and siloed project world of development where organizations are under pressure to reduce costs. This may lead to more funds available for disbursement directly to beneficiaries but does little to achieve the sought effects, let alone systemic change. Achieving impact in the form of system change requires smart and effective interventions built on continuous learning and adaptation and a facilitative role of development organizations.

We also go a step further in saying that learning and adaptation are not only necessary requirements for effective projects (i.e. at institutional level), but that societies as such require ‘systemic evaluation capacities’ that allow for more effective decisions in response to a more complex and dynamic world. Addressing the flows of knowledge and information between actors in targeted sectors where learning and adaptation needs to happen in response to challenges such as technological innovations, is a challenging task. Wealthier countries have established systems that generate and utilize knowledge more efficiently; other countries, including those in the Western Balkans, risk losing out in a competition that is increasingly about knowledge and skills rather than low costs.

Please note: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of NADEL and IPDET.

Read more on Impact and Learnings from Failure.

Subscribe to Helvetas Mosaic

Helvetas Mosaic is a quarterly published by Helvetas Eastern European team for our email subscribers and website visitors. Our articles explore new trends and fresh ideas of international development work in Southeast Europe.